My big brother died 25 years ago today, literally half my lifetime ago. It was the height of the AIDS epidemic, he was 33 and vulnerable, and that was that.

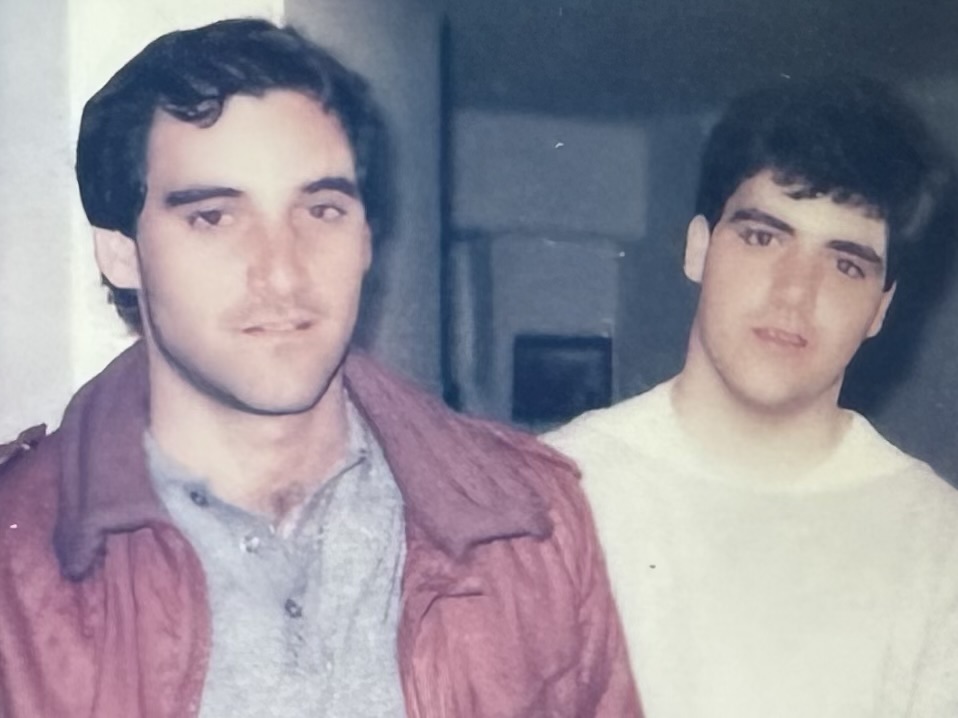

His name was James Bernard Grady, Jr., a.k.a. “JB.” In life, JB was a typical human — the kind of roommate who rarely washed out the sink after shaving and who ate all your Cheez-its without asking. But in death and in memory, JB has become, for me, Steve McQueen cool and James Dean tragic: the first kid on the block to buy the new Clash album, the first in line for the new Jim Jarsmusch movie at the Nickelodeon Cinema, the first one in his gang of artsy friends to really rock a Members Only jacket.

Thanks to the mercies of selective memory, I now recall my big brother as the confident rock star who played a gig at a hipster bar in Cambridge one night in 1980-something, and not as the annoyingly dedicated drumming student with whom I was forced to share a bedroom. Thump, thump, thump, tap, tap, tap. High-hat. Cymbal. Repeat. Ugh.

Still, despite the noise, I knew even then that my big brother was pretty damn cool. Sitting here now, a quarter century later, it occurs to me that my big brother has become less of a lost sibling to me and more like some kind of legendary celebrity I was lucky enough to have met several times when I was young and impressionable. Like a star-struck fan feverishly scouring e-Bay, I’ve curated little pieces of memorabilia from our short time together: his eclectic, punk-leaning vinyl album collection; his Kodachrome slides filled with off-kilter images of 1980s Boston; the black and white Swatch Watch he wore in the hospital that terrible, final week. These are among my most prized possessions. And like any true fan, I have a number of selfies with him, although they’re all pre-internet. Analog.

Like all of us, JB wanted to make an impact, to be remembered. He was a gifted weekend photographer and was working weekdays to become a probation officer, with the goal of helping damaged people get their lives back on track.

In life, he had (of course) a meaningful impact on me and my family. But it should be noted that, in death, JB had a profound impact on the lives of countless strangers. Just like a much-admired celebrity. Here’s how:

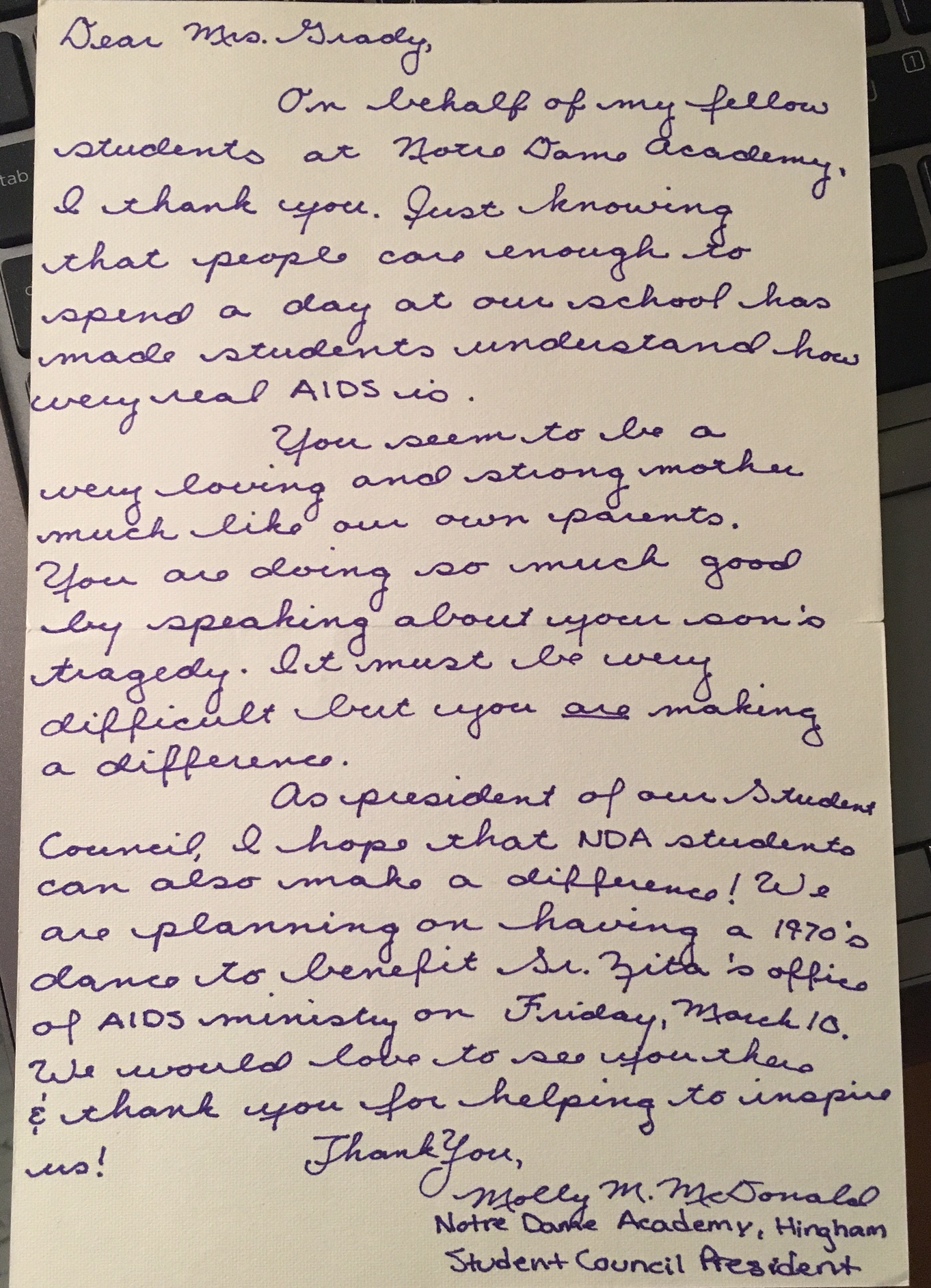

After a year of wrenching grief, my mother Marianna somehow pulled herself out of bed and hit the speaking circuit, talking with wide-eyed youth groups about AIDS — and telling the story of my brother’s life and needlessly-early death.

I never saw her speak, by choice. But I heard, consistently, that her talks were riveting, non-judgemental, and actionable. The kids in the audience left my mom’s talks knowing two things with certainty: that parents truly, madly, deeply love their children, and that every sex-and-drugs-and-rock-and-roll-related decision they’ll make will have real consequences, someday. Lessons learned, attitudes adjusted, the world was a slightly safer place for these kids after having heard my mom tell JB’s story in the context of a global epidemic. Not nearly enough people were talking to young adults this meaningfully and directly in the early 1990s.

How my mom found the energy to do this for more than a year at dozens of speaking events is beyond me; it pains me just writing about this two and a half decades later. And in her well-attended talks with young people at Catholic churches throughout New England, my mom momentarily brought JB back to life — and doubtlessly saved a few lives in the process. Witness the “thank you” note (below) from a local school’s student council president, circa 1994: “Just knowing that people care enough to spend a day at our school has made students understand how very real AIDS is….you are doing so much good by speaking about your son’s tragedy. It must be very difficult but you are making a difference…”

That’s a legacy way cooler than any collection of rare Clash records.

It’s been 25 years, JB, and I’m still star-struck.

Leave a reply to Paul Costantino Cancel reply